Pao Turgidus Pufferfish Care Sheet

- Macauley Sykes

- Oct 8, 2025

- 18 min read

Updated: Feb 11

This care sheet is written with the aim of providing the optimal care for this species of fish.

Pufferfish Enthusiasts Worldwide endeavours to inspire and promote the highest standards of care - not basic or minimum care - using the best evidence available at the time.

Introduction

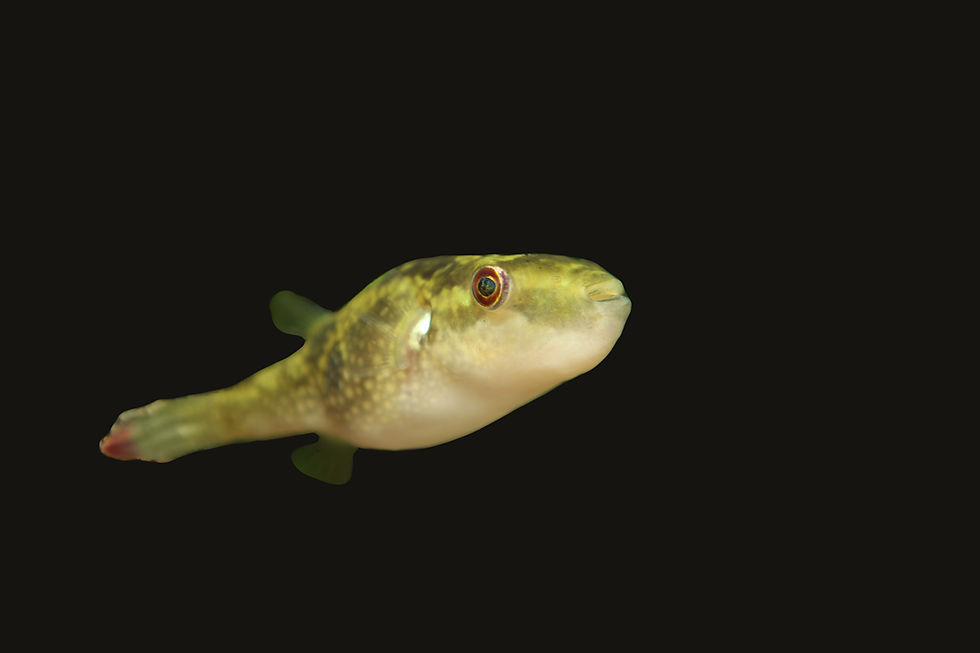

The Pao turgidus is one of the Mekong’s most intriguing yet overlooked freshwater puffers, a species that perfectly embodies the complexity of Southeast Asia’s great river systems.

Endemic to the Lower Mekong Basin, it is found across Thailand, Laos, Cambodia, and Vietnam, where it inhabits an ever-changing mosaic of floodplain channels, oxbow lakes, and vegetated margins.

Described by Maurice Kottelat in 2000 from the Mekong basin, Pao turgidus is one of several Southeast Asian freshwater pufferfish that have been reclassified as our understanding of the family Tetraodontidae has advanced. Originally placed in the broad genus Tetraodon (which historically included most pufferfish species), it was later recognised as belonging to a distinct Asian freshwater lineage. Kottelat’s 2013 revision of the region’s inland fishes formally recognised Pao as the valid genus for this group, separating it from Tetraodon and related forms on morphological grounds consistent with molecular evidence. Today, Pao turgidus is accepted as a valid species within Pao and represents a typical riverine member of this distinct freshwater lineage.

Reaching around 15–18 cm (6–7 inches) in length, it sits in the upper middle range for freshwater puffers, large enough to command presence, but not beyond what an experienced aquarist can responsibly maintain. Behaviourally, it is a classic Pao: deliberate, observant, and deeply aware of its surroundings. It watches, waits, and then strikes, displaying the precision of a born ambush predator.

Known variously as the Cambodian Mekong Puffer, Brown Puffer, Spotted Target Puffer, Asian Spotted Puffer, and Chameleon Puffer, this species remains rare in captivity but deeply rewarding to those who study or keep it. It offers not just the allure of rarity, but the chance to observe a fish whose story is written into the current of one of the world’s great rivers.

In the wild

Pao turgidus is native to the Mekong Basin, where it occurs across Cambodia, Laos, Thailand, and Vietnam. Reports from the Chao Phraya Basin remain unconfirmed, but within the Mekong system the species is both widespread and locally abundant, occupying the quieter margins of the river and its adjoining floodplains.

This species favours slow-moving or still waters with abundant structure. It is most often found in oxbow lakes, vegetated backwaters, and floodplain channels, where submerged roots, branches, and leaf litter create dense cover. Such environments provide camouflage and ambush points, allowing the fish to remain still for long periods before lunging at passing prey.

Detailed studies focused solely on P. turgidus are scarce, but extensive surveys of the Lower Mekong Basin offer valuable context for its habitat. Across these regions, the water is typically soft to moderately hard, with chemistry that fluctuates seasonally.

Typical field values recorded from representative habitats include:

pH: 6.0–7.8 (most sites 6.8–7.2)

Temperature: 22–30 °C, depending on season

Conductivity: 50–400 µS/cm

Dissolved Oxygen: moderate, occasionally low in still floodplain pools

These conditions reflect the calm, organically enriched environments this species prefers. The naturally low mineral content and steady input of leaf litter and sediment create mildly acidic water that shifts gently through the year with each flood and dry cycle.

Diet in the wild

Direct dietary analyses for Pao turgidus have yet to be published, but its feeding habits can be inferred with a fair degree of confidence. A combination of field observations from related species, morphological evidence, and toxin data all converge on the same conclusion: that this is a benthic hunter, adapted to exploit the rich invertebrate life of the Mekong floodplain.

Its anatomy leaves little doubt. Like other Pao, P. turgidus bears a heavily built jaw and fused dental plates that form a formidable beak, an adaptation evolved for crushing hard-shelled prey. Among its close relatives, wild fish have been recorded feeding on snails, crabs, insect larvae, and worms, and there is every reason to believe P. turgidus follows a similar pattern.

Throughout its range, potential prey are abundant. Freshwater snails of the families Viviparidae and Planorbidae, small Parathelphusa crabs, and the larvae of Chironomidae, Odonata, and Ephemeroptera all thrive among submerged vegetation and detritus in the river’s quieter reaches. Seasonal flooding likely influences its diet: in the wet months, when microcrustaceans and insect larvae proliferate across inundated floodplains, these softer-bodied organisms may dominate; in the dry season, the puffer probably depends more on snails and worms that persist in the shaded backwaters and slow-moving channels.

Occasional piscivory is possible. In congeners such as P. suvattii, small fish are sometimes taken when conditions are favourable, particularly during the high-water months when prey density peaks. For P. turgidus, such behaviour is best viewed as opportunistic, an extension of its generalist feeding strategy rather than a primary mode of predation.

Toxin studies lend further weight to this picture. Wild-caught P. turgidus have repeatedly tested positive for saxitoxin (STX), a potent neurotoxin produced by cyanobacteria and transmitted through the food chain (Saitanu et al., 2000; Yu et al., 2011). This accumulation strongly implies that its prey (especially snails and crabs), graze on algae and biofilms harbouring toxin-producing microorganisms, which are then assimilated by the puffer itself. The chemistry of its tissues, in effect, traces the ecology of its diet.

Taken together, these strands of evidence form a consistent portrait of P. turgidus as a benthic carnivore with opportunistic tendencies. It inhabits the same slow-moving margins and floodplain channels as Anabas testudineus, Channa striata, and Trichopodus trichopterus, participating in the same detrital food web that underpins the Mekong’s extraordinary productivity. In both structure and behaviour, it is a quiet, deliberate predator: an animal shaped by the cycles of flood and retreat that define its world.

Conservation Status

Pao turgidus is listed as Least Concern (LC) on the IUCN Red List, reflecting its broad distribution and presumed stable populations.

However, its habitats are increasingly affected by hydropower development, floodplain reclamation, and sediment alteration across the Mekong Basin. Although not directly threatened at present, its long-term resilience will depend on the conservation of slow-water habitats and the maintenance of natural flood cycles that sustain its prey base.

In the Aquarium

Although Pao turgidus has never been a common sight in the aquarium trade, it has begun to appear more frequently in recent years as interest in the freshwater puffers of Southeast Asia continues to grow.

All specimens reaching the market are wild-caught, but the species has shown a strong capacity to adapt to captivity when its environmental needs are understood and respected.

In temperament, P. turgidus is reserved and observant. It is primarily crepuscular, becoming most active during the soft light of early morning and late evening. For much of the time, it quietly rests among roots or within the shelter of plants.

Lighting should always be soft and atmospheric with diffused illumination that is filtered through floating plants, hardscape, or dappled by surface cover to best mirror the subdued conditions of the Mekong floodplain. Under harsh, direct light, P. turgidus often retreats into hiding, but in gentle, filtered light, it becomes noticeably more confident, gliding slowly through its territory with quiet assurance.

A well-structured layout is essential. This is not a fish that thrives in open water. When surrounded by cover, it becomes calmer, bolder, and far more interactive.

The aquascape should therefore be designed not as a display, but as a habitat: a natural composition of wood, stone, plants, and botanicals that allows the fish to decide when to be seen and when to disappear.

Begin with a substrate of fine sand, scattered with leaves, twigs, and fragments of natural debris to create a lived-in, organic appearance. Build upon this foundation using driftwood, root tangles, and branching hardwoods (such as Redmoor) to form arches, recesses, and overhangs that resemble the submerged margins this fish evolved along. These hardscape elements are not mere decoration, but structural anchors that shape how secure the fish feels in its environment.

Planting deepens this sense of immersion. In the shaded, slow-moving waters P. turgidus inhabits, vegetation is soft, layered, and diverse. Hardy, low- to moderate-light species such as Limnophila sessiliflora, Hygrophila polysperma, Hygrophila difformis, Ceratopteris thalictroides, or Ludwigia repens can be arranged into dense stands that divide the tank into sheltered zones. Broader-leaved plants such as Anubias barteri, Echinodorus bleheri, and Cryptocoryne wendtii complement these thickets, creating overhanging leaves and shadowed recesses where the puffer can rest. Floating plants such as Salvinia natans, Limnobium laevigatum, or Pistia stratiotes, complete the composition, forming a soft canopy that filters the light and adds a sense of calm enclosure. Their dangling roots foster microfauna and detritus, subtly enriching the ecosystem.

When arranged with care, this layered scape transforms P. turgidus from a shy observer into an active participant in its environment. Once it learns the layout of its territory and recognises that escape routes are always within reach, it will begin to venture out, exploring deliberately, watching movements beyond the glass, and responding to its keeper’s presence. Its confidence grows in proportion to the complexity of its surroundings.

Water movement should be slow to moderate. A light current that ripples the plants and maintains good oxygenation is sufficient; strong, directed flow is unnecessary and can cause stress. The ideal system reflects the backwaters and floodplain channels of the Mekong, calm and clear with plenty of microstructure.

When these conditions are met, P. turgidus begins to display its quiet personality. It will emerge during the dim hours, gliding between shadows with a sense of purpose, watching its keeper with calm awareness before returning to its refuge. There is a grace in its stillness and a dignity in its caution, qualities that remind us that not all beauty in the aquarium comes from colour or activity, but from the quiet authenticity of a fish truly at ease in its environment.

Tank size

Pao turgidus is not a particularly active swimmer. In the wild, it spends much of its time resting among roots, wood, and submerged vegetation, moving only when hunting or exploring its immediate surroundings. This relatively sedentary lifestyle means that it does not demand vast swimming space, but it does require stability, structure, and room for territory.

While not a species that demands a giant tank, P. turgidus thrives when given room to explore a carefully structured environment.

A single adult should be kept in a tank measuring at least 80 cm in length and 35–40 cm front to back, with a height of around 40 cm.

This provides a volume of approximately 110–120 litres (29–32 US gallons), offering sufficient space for dense planting, driftwood, and natural cover while maintaining excellent water stability.

As with all puffers, however, larger is always better.

A greater volume allows for more elaborate landscaping, improved waste dilution, and a wider range of behaviours. In more spacious aquaria, P. turgidus tends to be noticeably more relaxed and interactive, often venturing into open areas or following the keeper’s movements with calm curiosity.

Water values

Maintain the following water parameters:

pH: 6.5–7.5

Temperature: 24–28 °C

Ammonia (NH₃/NH₄⁺): 0 ppm

Nitrite (NO₂⁻): 0 ppm

Nitrate (NO₃⁻): Below 15 ppm (ideal)

General Hardness (GH): 3–12 dGH typical

Why these Numbers?

These recommendations reflect the conditions recorded across the Lower Mekong Basin, where Pao turgidus inhabits the quiet margins of rivers, channels, and oxbow lakes. Surveys of these waters show temperatures commonly between 24 and 30 °C, soft to moderately mineralised water, and a near-neutral pH that shifts only slightly with season and flow. Conductivity readings from vegetated margins average between 70 and 600 μS/cm, translating to roughly 3–12 dGH.

The chosen temperature band of 24–28 °C mirrors the heart of this range: warm enough to reflect the tropical climate, yet cool enough to preserve oxygen saturation and stable metabolism. pH between 6.5 and 7.5 suits the slightly acidic to neutral character of the Mekong’s backwaters while giving a safe margin for aquarium fluctuation.

Ammonia and nitrite should always remain at 0 ppm, as puffers are acutely sensitive to nitrogenous waste. Even trace levels can cause respiratory distress or rapid appetite loss. Maintaining nitrate below 15 ppm is a measure of water cleanliness rather than strict toxicity; it helps sustain long-term vitality and prevents the low-grade stress associated with chronic exposure to nitrogen compounds.

While P. turgidus is tolerant of a modest mineral range, its best colours and behaviour emerge in soft, clean water with gentle movement and steady oxygenation. Flow should be minimal, enough to circulate and prevent stagnation, but never strong. High dissolved oxygen and low organic load are more important than current strength.

Tankmates

Pao turgidus should be regarded as a solitary species.

Although calmer than many of its relatives, it remains a deliberate ambush predator that will attempt to eat any fish small enough to swallow and may injure or kill larger companions.

For this reason, it is best kept alone. Solitary care allows it to behave naturally and remain calm, without the stress of defending territory. A single specimen in a well-structured aquarium is far more likely to display its intelligent, observant character than one kept in company.

Breeding attempts are possible but unpredictable. Behaviour between conspecifics can shift rapidly from tolerance to aggression, so any pairing should be approached with extreme caution and only by experienced keepers.

Sexual dimorphism

There is currently no reliable external method to determine the sex of Pao turgidus. Scientific literature reports no consistent visual differences between males and females, and aquarium observations have not revealed any dependable traits related to colour, pattern, or body shape.

Apparent differences in fullness or body width are usually linked to feeding state rather than sex.

Occasional claims from keepers of other Pao species suggest that males may appear slightly slimmer or develop more angular heads, but these remain anecdotal and have not been verified for P. turgidus. At present, accurate sexing can only be achieved through internal examination or advanced imaging techniques, which are not practical for general husbandry.

For anyone attempting to breed this species, it should therefore be assumed that individuals cannot be sexed visually. Any introductions must be carried out with extreme caution, as behaviour between conspecifics can change rapidly and aggression is common.

Notable behaviour

Pao turgidus is a fish of quiet intent. In its natural habitat, it spends long periods resting motionless among roots and driftwood, blending perfectly into its surroundings. It is not lazy, but patient. Every slow turn of the eye and subtle shift of the fins hints at awareness, as if it is constantly reading the world around it.

Activity peaks during the early morning and late evening, when the light softens and the fish begins to patrol its territory. It moves with calm precision, inspecting the substrate, pausing beneath branches, and rising occasionally into open water before returning to cover. This crepuscular rhythm is deeply ingrained and remains consistent in the aquarium. When lighting is subdued, P. turgidus becomes noticeably bolder, exploring with purpose and confidence.

It is a species that thrives on familiarity. Over time, it develops a distinct sense of routine, responding to regular feeding times and environmental cues. Many keepers note that their fish appear to anticipate activity in the room, emerging when they hear familiar sounds or see movement near the aquarium. This attentiveness, combined with its steady gaze and deliberate movements, gives P. turgidus a personality that feels unusually perceptive for a fish.

When settled, P. turgidus displays a calm confidence that makes it captivating to watch. It may hover in midwater for minutes at a time, fins gently rippling, or rest partly buried in sand, perfectly still except for the slow pivot of its eyes. It does not startle easily once accustomed to its surroundings, but sudden disturbances can prompt an instant retreat into cover.

In a peaceful, well-structured aquarium, these small details come together to reveal the species’ true nature: deliberate, watchful, and quietly intelligent. Observing Pao turgidus is an experience in subtlety, one that rewards patience and attentiveness from the keeper as much as it does from the fish itself.

Feeding

Feeding P. turgidus is a subtle, almost meditative experience. This is not a fish that rushes to its food or lunges in frenzy. It approaches every meal with calm deliberation, as though weighing its options before committing to a strike. It studies the movement of its prey, angles itself with quiet precision, and then advances in a smooth, controlled burst: powerful but never clumsy. Watching it feed reveals an animal that is both cautious and deeply intelligent, perfectly adapted to a world of slow currents and soft light.

Over time, its personality becomes unmistakable. A well-settled P. turgidus learns its keeper’s presence, emerging from beneath branches or leaves as soon as familiar faces approach. It follows movement beyond the glass with a steady, unblinking gaze, often holding position midwater as if listening to its surroundings. These small, deliberate gestures give it a presence that feels almost contemplative. When conditions are right, it displays a calm confidence that makes it one of the most rewarding freshwater puffers to keep, not for spectacle or colour, but for the quiet connection it forms through recognition and routine.

Although we lack a comprehensive gut-content analysis of wild individuals, our understanding of Pao turgidus’s dietary needs has evolved considerably thanks to studies identifying saxitoxin (STX) in the tissues of wild specimens. From these findings, we can safely assume that this species feeds within a freshwater, cyanobacteria-linked food web, consuming gastropods, small crustaceans, insect larvae, and other benthic invertebrates that graze upon or ingest cyanobacteria. These organisms act as natural toxin vectors, transferring STX through the food chain. In this way, the chemistry of the fish itself provides insight into its ecology, revealing a diet rooted in the silty, organic margins of the Mekong where such prey are abundant.

Based on habitat overlap and toxin transfer pathways, it is likely that the natural diet includes viviparid and bithyniid snails (Filopaludina martensi, Bithynia s. goniomphalos), Asian clams (Corbicula fluminea), Macrobrachium prawns, Somanniathelphusa crabs, and chironomid larvae. Many of these are known saxitoxin carriers, aligning precisely with what has been detected in wild fish.

Across the internet, feeding advice for Pao species has long been inconsistent and often speculative. Many early guidelines were based on generalised carnivore care rather than direct evidence, leading to confusion over the balance of fish, invertebrate, and hard-shelled foods these species require. At Pufferfish Enthusiasts Worldwide, our recommendations are evidence-led, drawing from ecological research, toxin studies, and long-term observation of captive individuals.

Recommended Foods:

Freshwater snails of varying sizes (pond, ramshorn, and similar species)

Frozen-thawed freshwater crabs and crayfish

Gut-loaded earthworms, blackworms, and bloodworms

Gut-loaded cockroaches, crickets, and locusts.

Thiaminase-free fish fillet or small fish pieces, offered occasionally for variety

Occasional small aquatic insects or daphnia for behavioural enrichment

Avoid relying on marine-derived foods such as mussels, cockles, clams, oysters, or prawns as dietary staples. These items differ nutritionally from the freshwater invertebrates that P. turgidus consumes in the wild and are often high in thiaminase, an enzyme that destroys vitamin B₁ (thiamine). When used in excess, thiaminase-rich foods can contribute to long-term vitamin deficiency and loss of appetite.

Suggested Feeding Breakdown

To maintain balance and variety while reflecting the natural diet structure, the following approximate ratios are recommended:

30% freshwater snails and other molluscs

25% freshwater crustaceans (crab & crayfish pieces)

25% worms and insects (earthworms, blackworms, bloodworms)

15% thiaminase-free fish and soft protein

5% enrichment foods (small aquatic insects, daphnia, or occasional treats)

These ratios provide a practical framework for feeding while ensuring that hard-shelled prey are offered regularly for dental maintenance and that soft foods form a varied and digestible staple.

Feeding fish

Fish flesh can be used to add variety to the diet of Pao turgidus, but it should be offered sparingly. In the wild, this species feeds mainly on aquatic invertebrates and only occasionally takes small fish. In captivity, the goal is to reflect that same balance.

When feeding fish, it is essential to choose thiaminase-free species. Thiaminase breaks down vitamin B₁ (thiamine), and long-term exposure can lead to deficiency, appetite loss, and neurological problems.

Recommended Fish Species

Excellent thiaminase-free and nutritionally safe choices include:

Tilapia (Oreochromis spp.)

Trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss)

Cod (Gadus morhua)

Pollock (Pollachius spp.)

Haddock (Melanogrammus aeglefinus)

Catfish (Ictalurus, Pangasius)

Pike or Perch, when cleanly sourced from freshwater

Frozen Pond Smelt (Hypomesus olidus) can also be used, as it is thiaminase-free and appropriately sized. Be aware that other smelt species, such as Rainbow Smelt (Osmerus mordax), do contain thiaminase and should be avoided.

Foods to Avoid: goldfish, minnows, anchovies, sardines, herrings, and most other smelts, as these are thiaminase-positive and unsuitable for long-term feeding.

Preparation

Because most market fish are too large to feed whole, proper preparation is essential:

Remove the head, fins, and internal organs.

Fillet the fish, leaving scales and skin intact.

Cut fillets into bite-sized chunks that can be swallowed within one minute.

Freeze prepared pieces for at least seven days to kill parasites.

Store frozen portions for up to three months and thaw naturally in cool water before feeding.

Feed with feeding tongs to control portion size and prevent waste. Offer fish only once every week or two, alternating with the invertebrate-based foods that form the main diet.

Feeder fish

We strongly discourage using live feeder fish for Pao turgidus. Feeder fish are often raised in crowded, stressful conditions where parasites (Ich, Trichodina, Gyrodactylus, Dactylogyrus, and Camallanus worms) and bacterial infections such as Flavobacterium columnare (Columnaris) are common. Introducing feeder fish into your tank significantly raises the risk of transmitting pathogens to your puffer.

Feeding live fish can also lead to behavioural problems, encouraging puffers to associate only movement with feeding and reject frozen or prepared foods. It is far safer to use frozen-thawed fish, freshwater crustaceans, and gut-loaded invertebrates, which provide the same hunting stimulation without the health risks.

Once settled, P. turgidus adapts readily to prepared diets and will usually accept frozen or fresh foods within a few days, making live feeders unnecessary for successful long-term care.

Tong Training

Tong training is one of the most valuable skills a keeper can develop when caring for Pao turgidus. More than a feeding technique, it is a way of building understanding and trust between fish and keeper. This intelligent, observant puffer quickly learns to associate the tongs with safety and food, turning what might otherwise be a cautious interaction into a confident, cooperative routine.

A tong-trained P. turgidus is easier to feed, easier to monitor, and noticeably more engaged. Each meal becomes an opportunity for calm interaction, allowing the keeper to observe behaviour closely and ensure every portion is eaten. The precision it provides helps prevent overfeeding and keeps the aquarium cleaner, while also guaranteeing that the fish receives the correct balance of nutrients.

Behaviourally, tong training encourages confidence. Once P. turgidus recognises the tongs, it begins to emerge more readily from its shelter, watching and waiting at the glass as the keeper approaches. This not only simplifies feeding but also strengthens the bond between them, turning mealtime into a moment of recognition and trust.

For a species as thoughtful and deliberate as P. turgidus, tong training is as rewarding for the aquarist as it is for the fish. It transforms feeding from a chore into a shared experience, one that deepens the relationship and brings out the species’ gentle intelligence in full view.

Filtration and Tank Maintenance

Although not an active swimmer, P. turgidus produces a substantial amount of waste for its size, and water quality can deteriorate quickly without consistent upkeep. A large external canister filter is ideal for most aquaria, offering both the biological volume needed for waste processing and fine mechanical polishing to keep the water clear. In larger systems, a sump can provide even greater stability, excellent gas exchange, and the opportunity to hide heaters and other equipment out of sight.

Flow should be gentle but continuous, circulating water evenly through the aquarium without creating turbulence. This maintains oxygenation and prevents debris from collecting while keeping the calm surface and soft currents this fish prefers.

No filtration system can replace regular care.

Clean, stable water is the foundation of success:

Keep nitrate below 15 ppm, ideally closer to 10 ppm.

Change at least 50% of the water weekly, increasing frequency for heavier feeding.

Lightly vacuum the substrate during changes, especially beneath wood and plants. In heavily structured tanks, detritus can settle beneath driftwood or in plant bases. Gentle circulation prevents this, keeping the water bright and oxygen-rich without disturbing the fish’s sense of stillness.

Why Keep Nitrates Low?

Like all puffers, Pao turgidus is highly intolerant of long-term nitrate accumulation.

Studies on freshwater fishes show that chronic nitrate exposure can lead to:

Suppressed immune function, increasing vulnerability to parasites and bacterial infections

Reduced growth and feed efficiency, limiting condition and vitality

Shortened lifespan and long-term health decline

In the wild, seasonal flooding of the Mekong constantly dilutes organic waste and refreshes the water column. In captivity, that same renewal must come from the keeper. Regular water changes, strong biological filtration, and careful feeding recreate the stability this species depends on.

For P. turgidus, clean, low-nitrate water is not just about survival. It is the foundation of its health, confidence, and colour. When water quality is maintained to this standard, the fish displays its full natural character: calm, aware, and quietly interactive.

Inflation

Pao turgidus possesses one of the most remarkable defence mechanisms in the freshwater world, the ability to expand its body when alarmed. By drawing in water, or in rare cases, air, it can swell to several times its normal size. This sudden transformation makes it appear larger, rounder, and far more difficult for a predator to grasp or swallow.

In the aquarium, inflation is a reflexive response to stress, not a normal behaviour. It should never be encouraged or provoked for amusement. The act places significant strain on the fish’s body and can be dangerous if air is accidentally taken in. Air inflation prevents the fish from submerging and can be life-threatening if not resolved.

That said, aquarists occasionally observe what is known as practice puffing. A calm and settled P. turgidus may gently inflate for a few seconds with no clear trigger, then return to normal size. This is believed to help stretch the skin and exercise the muscles associated with inflation. These brief, controlled episodes are harmless and do not indicate stress.

True defensive inflation, by contrast, occurs in moments of alarm or discomfort. If this happens, the fish should be left undisturbed so it can deflate naturally once it feels safe.

Prolonged or repeated inflation usually signals an underlying problem such as:

Poor water quality (ammonia, nitrite, or elevated nitrate)

Sudden lighting or vibration near the tank

Aggression or territorial stress

Rough handling during transfers or netting

Whenever P. turgidus needs to be moved, it should be gently guided into a container of water rather than lifted with a net. Keeping the fish submerged prevents panic and avoids the risk of air entering the body cavity.

A relaxed P. turgidus will rarely inflate outside of brief practice puffs. When this fish lives in a clean, calm, and stable environment, its need for this extraordinary defence almost disappears, a true sign that it feels secure and at home.

Toxicity and Toxin Origin

Scientific research on Mekong populations has confirmed that Pao turgidus carries paralytic shellfish toxins (PSTs) in the wild, most notably saxitoxin (STX) and decarbamoyl-saxitoxin (dcSTX). Analyses of specimens collected in Cambodia found the highest concentrations in the skin and ovaries, with recorded values of approximately 37 MU/g in skin and 27 MU/g in ovary. Tetrodotoxin (TTX) was not detected. Laboratory-reared individuals were completely non-toxic, demonstrating that toxin accumulation occurs through diet rather than internal synthesis.

Further genomic and chemical profiling of Cambodian Pao species has reinforced this finding. Freshwater puffers from the Mekong region show toxin profiles composed solely of STX and its analogues such as neoSTX and dcSTX, with TTX consistently absent. The levels vary between locations and tissues, reflecting differences in environment and diet.

Pao turgidus does not produce saxitoxin on its own. Instead, it acquires these compounds indirectly through the food web. The most likely sources are cyanobacteria and other microorganisms that naturally generate PSTs. These toxins pass through small crustaceans, molluscs, and other benthic invertebrates, which the puffer then consumes. Over time, the compounds build up within its tissues through bioaccumulation.

Comparative studies between marine and freshwater pufferfish reveal a clear ecological divide. Marine species typically accumulate tetrodotoxin, while freshwater Pao species concentrate saxitoxin and related analogues, reflecting differences in habitat chemistry, microbial communities, and diet.

Implications for Aquarists

For aquarists, this information is primarily of scientific interest rather than practical concern. In captivity, the cyanobacteria and prey species responsible for saxitoxin production are absent, and prepared foods contain no toxin precursors.

As with all puffers, the only realistic danger is through ingestion, not contact.

Routine maintenance, feeding, or tank interaction poses no risk whatsoever.

Disclaimer

The health and husbandry information provided in this guide is intended for educational purposes only. It should not be taken as, or replace, the advice of a qualified aquatic veterinarian.

If your pufferfish shows signs of illness or is experiencing a medical emergency, seek assistance from an experienced aquatic veterinary professional without delay.

© Copyright - 2025. All rights reserved.

Comments